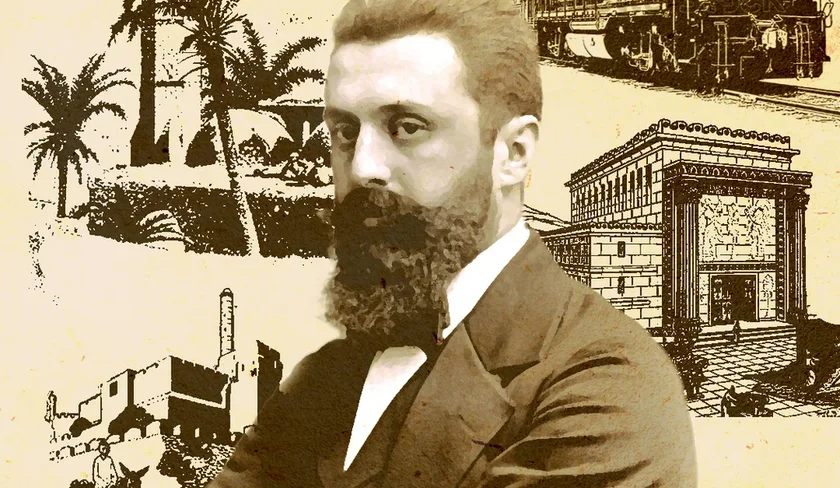

How did Theodor Herzl envisage the Jewish state in his 1902 novel ‘Altneuland’? Not an awful lot like it actually is 120 years later

Precisely 120 years ago, in 1902, Theodor Herzl published his vision of the Jewish state – 15 years before the Balfour Declaration, which promised a homeland for the Jews in Mandatory Palestine, and 45 years before the United Nations approved the partition plan, paving the way for the establishment of the State of Israel.

In honor of the anniversary, the original manuscript of Herzl’s utopian novel, “Altneuland,” is now on display at the Herzl Museum in Jerusalem. “Today too, 120 years on, this text has managed to remain relevant thanks to Herzl’s ability to already envision what would preoccupy the state,” proclaimed a statement by the World Zionist Organization’s Herzl Center.

But a detailed study of the book reveals a major gap between Herzl’s vision and aspirations and the reality. In fact, it shows the visionary inadvertently prophesying a number of the most basic problems of the Jewish state.

“Altneuland” (German for “The Old-New Land”) was published in Leipzig after Herzl’s visit to the Holy Land. In it, he describes a future journey to the Jewish state in 1923. But the work reveals no hint of the Jewish-Arab conflict in Israel. In fact, one of the characters in the book – an Arab by the name of Reschid Bey – praises the arrival of Jews to the country and remarks on their contribution to the development of the Arabs. “Our profits have grown considerably. Our orange transport has multiplied tenfold. … Everything here has increased in value since your immigration,” he says.

Although Herzl does not avoid the tough questions, his answers do not conform to the resultant reality. For example, in a dialogue with Bey, visitors to the country ask: “Were not the older inhabitants of Palestine ruined by the Jews’ immigration? And didn’t they have to leave the country?”

Bey does not speak of refugees, military rule, discrimination and racism. Instead, he responds: “You speak strangely, Christian. Would you call a man a robber who takes nothing from you, but brings you something instead? The Jews have enriched us. Why should we be angry with them?”

He also says, “Those who had nothing stood to lose nothing, and could only gain. And they did gain. … Nothing could have been more wretched than an Arab village at the end of the 19th century.”

It is possible to travel directly, without change of cars, […] from Amsterdam, Calais, Paris, Madrid or Lisbon to JerusalemTheodor Herzl in ‘Altneuland’

The only nationalist sentiment Bey displays in his encounters with Jews manifests itself in his protest over the insistence that “we Jews introduced cultivation here.” To this, Bey answers: “Pardon me, sir! But this sort of thing was here before you came – at least there were signs of it. My father planted oranges extensively.” But his words, according to the writer, were said “with a friendly smile.” Riots? Terror attacks? Not a trace.

‘No distinctions’

Herzl was not wrong only about the Jewish-Arab conflict. In fact, his vision crumbles in almost all its aspects, large and small. “My associates and I make no distinctions between one man and another. We do not ask to what race or religion a man belongs. If he is a man, that is enough for us,” says the Jew David Littwak, one of the book’s main characters.

“In your New Society, every man may live and be happy in his own way,” says another character in the book, Friedrich, who is touring the country. The description of the daily lives of the inhabitants is also lacking, to put it mildly. While the inhabitants of modern-day Israel are stuck in traffic jams from dawn till dusk, Herzl had a simple solution: an “electric overhead train … because they make street traffic safer and easier.”

The book describes one as “a large iron car running along the tops of the palms.” This old-fashioned solution seemed to Herzl most suitable to the reality in Israel, and indeed has recently been adopted in Haifa.

Moreover, in Herzl’s vision, anyone wanting to leave the country had no need to dash to the airport. Instead, people would be able to take a passenger train linking the land to the entire world: “It is possible to travel directly, without change of cars, from Saint Petersburg or Odessa, from Berlin or Vienna, from Amsterdam, Calais, Paris, Madrid or Lisbon to Jerusalem. The great European express lines all connect with the Jerusalem line, just as the Palestinian railways in turn link up with Egypt and Northern Africa,” he writes.

To Herzl’s credit, it should be noted that he correctly predicted the move to electric trains, even if it is only taking place 120 years after he wrote his novel. “When the visitors remarked that the locomotive had no smokestack, they were told that this line, like most of the Palestinian railways, was operated by electric power,” he writes.

But here too, he misses the mark when he describes the comfort of train travel. Third-class passengers, he states, are not tormented by overcrowding as in the past.

Crossing paths in Haifa

One of Herzl’s saddest predictions concerns the Galilean city of Tiberias, which he calls “a new gem” – without guessing how neglected it would be 120 years later. Herzl describes fine streets and plazas with mansions, a small bustling port, grand mosques, churches with a Roman or Greek cross, and fine stone synagogues, villas, hotels and gardens.

Herzl waxed poetic when describing Tiberias: “The vivid pageant reminded them of the Riviera between Cannes and Nice at the height of the season. Fashionable folk were driving in elegant little equipages of all kinds – mostly motor cars with seats for two, three, or four passengers.”

Haifa is called a “wonderful city,” a crossroad that “thronged with people from all parts of the world,” a mixture of Chinese, Indians and Arabs. Here too, he was reminded of the French Riviera, but with cleaner and more modern buildings. The traffic, “though lively, was far less noisy.” Even the streets were relatively quiet. The reason for this, he notes, is “partly to the dignified behavior of the many Orientals, but also to the absence of draught animals from the streets.”

Herzl placed his vision of the Temple in Jerusalem, which he described as a “wonderful structure of white and gold, whose roof rested on a whole forest of marble columns with gilt capitals.” He resolved the question of the holy sites with ease: physical ownership was not important, he declared. Religious sentiment would best be satisfied if holy places were not under the ownership of any one country.

Herzl’s vision of the health care system excluded no one. Hospitals were connected by central phone lines and coordination would prevent a temporary lack of beds. “If one hospital is full, an ambulance in its courtyard will at once take an applicant to another where beds are available,” he dreams.

In general, life in Herzl’s Jewish state is very comfortable one. There is no army, education is free (including university), there is harmony between Jews and Arabs, and there is not a trace of Jew hatred in Palestine or anywhere in the world.

In Herzl’s vision, even those who are discriminated against don’t suffer because of it. Reschid Bey’s wife, Fatma, for example, could not leave her house, which Herzl describes as peaceful and enclosed. “You must not think that that makes Fatma unhappy,” a Jewish character, Sarah, says. “I can understand that very well. … If my husband wished it, I should live just as Fatma does and think no more about it.”

Herzl’s technological predictions do not seem particularly accurate either. To cool down on hot days, “you will find blocks of ice even in the most modest homes,” or “wreaths of flowers in ice for the dinner table.” And to keep abreast of current events, people would use a “telephonic newspaper.” There is no mention of the screens that have taken over our lives.

Herzl does not mention Tel Aviv in “Altneuland” because it had not been established when his book was written. But the book did make a significant contribution to the city. Nahum Sokolov, who translated “Altneuland” into Hebrew, called the book “Tel Aviv” – to combine the idea of an old place with antiquities (“Tel”) and the newness of spring (“Aviv”).