New guidance calls for Church of England to review monuments for ‘contested heritage’ and relocate or remove them

The Church of England is to review thousands of monuments in churches and cathedrals across the country that contain historical references to slavery and colonialism, with some expected to be removed.

Guidance to be issued this week encourages the C of E’s 12,500 parishes and 42 cathedrals to scrutinise buildings and grounds for evidence of contested heritage, and consult local communities on what action to take.

Although decisions will be made at a local level, the guidance stresses that ignoring contested heritage is not an option. Among actions that may be taken are the removal, relocation or alteration of plaques and monuments, and the addition of contextual information. In some cases, there may be no change.

The guidance comes after Justin Welby, the archbishop of Canterbury, called for a review of the C of E’s built heritage following the Black Lives Matterprotests last summer and the toppling of a statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol. “Some [statues and monuments] will have to come down,” Welby said at the time.

An anti-racism taskforce set up by the archbishops of Canterbury and York last month urged the C of E to take decisive steps to address the legacy of its involvement in the slave trade. It said: “We do not want to unconditionally celebrate or commemorate people who contributed to or benefited from the tragedy that was the slave trade.”

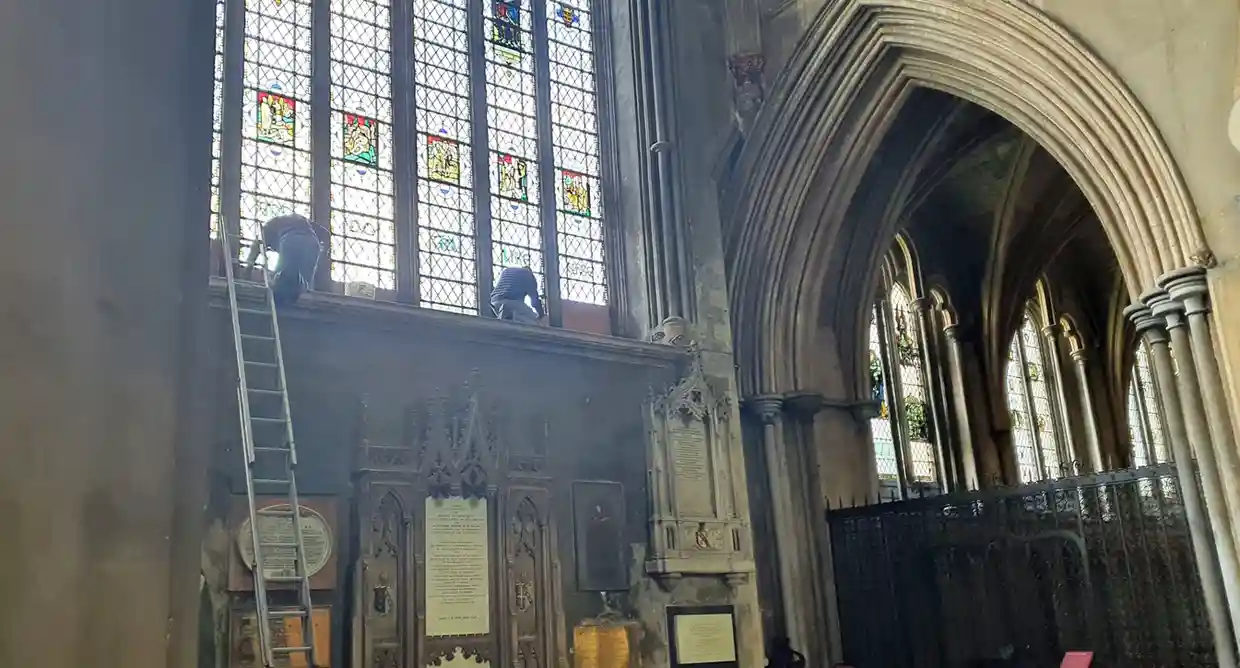

Action has already been taken in a number of places. Bristol Cathedral has removed a window dedication to Colston; St Margaret’s church in Rottingdean, Sussex, has removed two headstones in its graveyard which contained racial slurs; and St Peter’s in Dorchester has covered up a plaque commemorating a plantation owner’s role in suppressing a slave rebellion.

Becky Clark, the C of E’s director of churches and cathedrals, who produced the guidance, told the Observer: “Our church buildings and cathedrals are the most visible part of the C of E, a Christian presence in every community. The responsibility to ensure they include, welcome and provide safe spaces for all is a vitally important part of addressing the way historic racism and slavery still impacts people today.”

The guidance is likely to be controversial, both among those who call for all contested heritage to be removed, and those who say such heritage is an important part of the nation’s history.

But Clark said the guidance sought to “empower rather than shut down conversation”. Rather than being prescriptive, it was intended to steer parishes through the process of evaluating built heritage and determining what action to take.

“It doesn’t make political statements, except to say the history of racism and slavery is undeniable, as is the fact that racism and the legacy of slavery are still part of many people’s lives today. Responding to those in the right way is a Christian duty. Doing nothing is not an option. There has to be engagement with this.

“The job of local parishes is to figure out how this impacts our communities today. Are there people who feel this church is not for them because of the built heritage, and what can we do about it?”

As well as statues and monuments that “celebrate or valorise those involved in the slave trade”, there were also “simple memorials to somebody who was loved by their family”, she said.

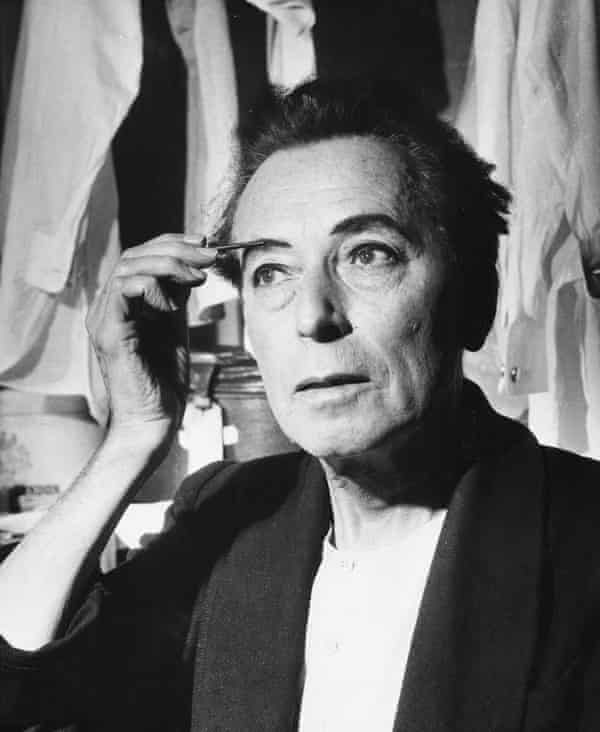

At St Margaret’s Rottingdean, a Grade II listed 13th-century church on the Sussex coast, the gravestones of two music-hall singers who died in the 1960s have been removed following a consistory court judgment that their inscriptions contained words that were “deeply offensive”.

Although the flint-walled churchyard is the legal responsibility of the parish priest, the headstones are the property of the descendants of GH Elliott and Alice Banford, who wore blackface in their performances. A judgment in February by Mark Hill, chancellor of the diocese of Chichester, said the descendants had been traced and had agreed to the stones being recut to remove the “derogatory and racist” term.

Hill added: “Mindful of the public interest (and hostility in some parts) concerning this matter, it would be inappropriate to direct the immediate reinstatement of the headstones.” He suggested the work be completed within two years, although the time period could be extended.

At Bristol Cathedral, a dedication to the 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston has been covered and will be eventually replaced with plain glass. Additional information about Colston, the slave trade and C of E’s links to slavers will be provided. The cathedral is also carrying out a comprehensive audit of monuments and plaques with slave or colonial references.

The window was created in the Victorian era to memorialise Colston’s philanthropic efforts, said Mandy Ford, the cathedral’s dean. “Bristol Cathedral was fundamentally enlarged by Victorian philanthropists in the 1860s. Many of those people made their money through trading to Africa or India, and we have a number of memorials to families who were plantation owners.”

Ford, who was appointed a year ago, said there had been “two or three false starts” in dealing with the complexities of contested heritage. “This can’t be another one. Let’s not be mistaken – this is one element of the issues we have to face around institutional racism, the failure of the C of E to be the church of the people. This is part of a bigger picture about diversity and inclusion, about who feels welcome. We want to be a place where everybody feels they can come.”

A Dorchester church has covered a plaque commemorating an 18th-century slave owner pending its removal. The inscription on the plaque at St Peter’s church celebrates the role played by John Gordon, a plantation owner, in “quelling” a slave rebellion in which hundreds were killed.

A notice placed over the plaque says the memorial “commemorates actions and uses language which are totally unacceptable to us today”. The plaque is to be offered to a museum.