The federal court case could have a sweeping impact on Native families and tribal sovereignty.

In June 2016, a 10-month-old Navajo and Cherokee boy was placed in the home of a white, evangelical couple in Fort Worth, Texas.

The baby had been taken from his Navajo mother, who’d left the reservation and was living in Texas, because of her drug use. The foster couple — Jennifer and Chad Brackeen, an anesthesiologist and a former civil engineer — were “self-conscious about their material success,” the New York Times reported, and told the paper that fostering a child was a way to “rectify their blessings.”

The next year, the Brackeens were temporarily held back in their plans to adopt the boy, when, under the provisions of the Indian Child Welfare Act, the Navajo tribe located a Native family unrelated to the boy to take him in. So the Brackeens filed a federal lawsuit. “He had already been taken from his first home, and now it would happen again? And the only explanation is that we don’t have the right color of skin? How do we explain that to our own children? We’d done nothing but sign up to do good,” Jennifer Brackeen told the Times.

Since the suit was filed, plans to send the boy to another tribe fell through and the Brackeens have been allowed to formally adopt him. Last year, the Brackeens fought to obtain custody of the boy’s sister, whose Navajo extended family wanted to take her in. At the hearing deciding the girl’s fate, Chad Brackeen left out any self-consciousness about his large home with a pool on an acre of land that he had expressed to the Times. He told the judge that he worried for the baby girl, “not as an infant living in a room with a great-aunt but maybe as an adolescent in smaller, confined homes.”

“I don’t know what that looks like,” he continued, “if she needs space, if she needs privacy. I’m a little bit concerned with the limited financial resources possibly to care for this child, should an emergency come up.”

This cultural difference — that a family’s fitness is determined by its wealth, and that those concerns should outweigh a child’s connection to their family and heritage — is essentially why the Indian Child Welfare Act was created in 1978. The law recognizes the history of federal policy aimed at breaking up Native families and mandates that, whenever possible, Native families should remain together.

Sarah Kastelic, the executive director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association, said that ICWA acknowledges important familial and tribal bonds that have long been disregarded, and that Native ways — such as extended families living under the same roof — have often been used to show unfitness in child welfare proceedings. “No matter the picket fences and swimming pools and things, most of the time, kids want to be with their families,” she said.

With their lawsuit, in which they’re joined by the State of Texas, the Brackeens have become the public face of the case that could dismantle ICWA. The couple — and the Goldwater Institute, the conservative think tank who backed the lawsuit — scored a win in 2018 when a federal district court ruled that ICWA was unconstitutional. Last year, a Fifth Circuit panel of three judges partially reversed the decision. Then, last month, the case was taken up by all 17 judges on the Fifth Circuit in an “en banc” hearing; Native advocates say it’s likely that whatever the ruling, the decision will be appealed to the Supreme Court.

If overturned, the repeal of ICWA could upend a law in place for more than 40 years. And the legal case has much broader implications than just child welfare — it cuts at the heart of tribal sovereignty in this country. The 573 federally recognized tribes could be left open to legal challenges on many fronts if the basis of ICWA is found unconstitutional.

“The core of their argument is that it’s an unfair racial preference and that we should have a colorblind system,” Chuck Hoskin Jr., the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, told Vox. “What that misses is what’s a bedrock of federal Indian law in this country, which is that tribes are sovereign, not distinguished as a race but as a special political designation. That’s a critical underpinning of not just ICWA, but many laws that relate to housing and healthcare and education and employment. For that to be eroded by a successful attack on ICWA — that would have broad implications on all of these.”

Kastelic said that ICWA has long been subject to lawsuits from two groups — those with the ultimate goal of eroding tribal sovereignty, and those in the adoption community who disdain the lengthier process that must be undertaken to adopt a Native child.

“We’ve seen the rise of think tanks — Goldwater Institute, Heritage Foundation, Cato — that have a broader agenda about state rights and subverting or dismantling tribal sovereignty as part of their agenda,” Kastelic said. “And then there’s a religious agenda, a number of Christian organizations wanting access to Native children still with the premise of ‘saving Indians’ — that because of high rates of poverty or substance abuse or mental health challenges, that that still warrants them to take our children. They feel entitled to them.”

The US’s long, disgraceful history of breaking up of Native families

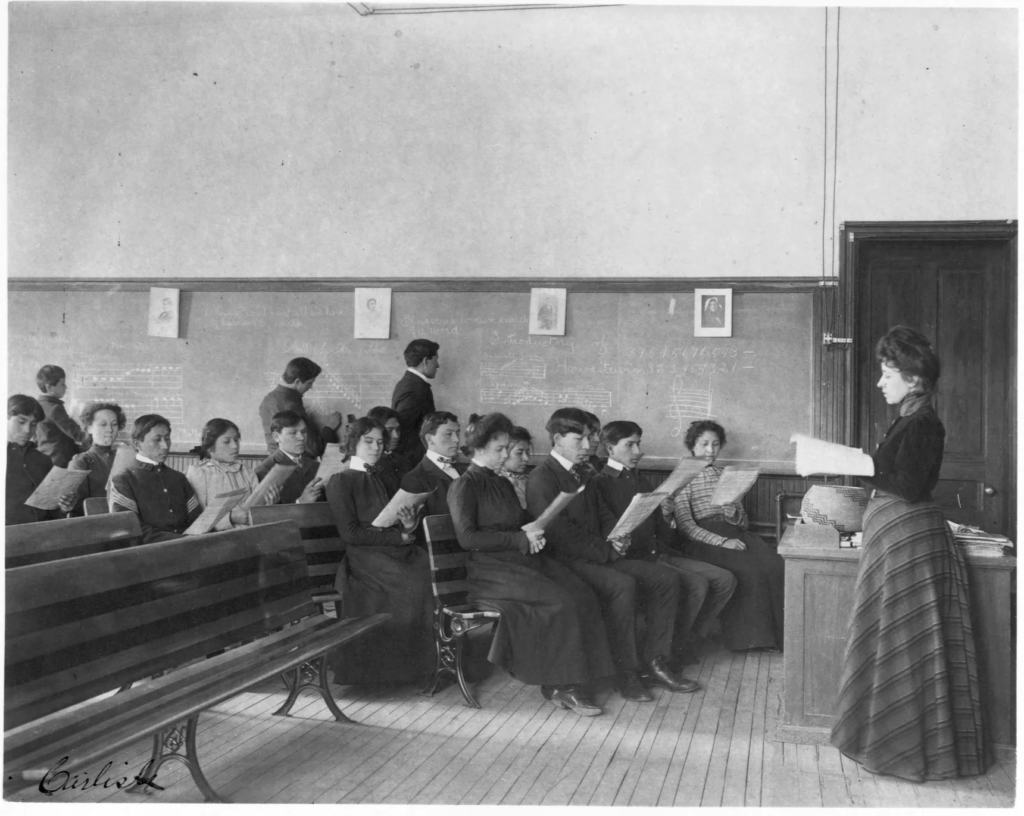

Forced removals of Native Americans from their homelands by the federal government in the 1800s caused the deaths of thousands of Native American people, especially children and the elderly. In 1879, the federal government undertook a mass assimilation effort of Native children, creating Indian Boarding Schools, in which Native children were forced to drop their language and customs and were indoctrinated in white American ways. Many in the boarding schools suffered abuse — 180 graves of children can be found on the grounds of the single most famous school of that era, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

When the boarding schools began to die out in the 1950s and 1960s, a new effort took its place. From 1958 to 1967, the federal government enacted a program called the Indian Adoption Project, with the goal of white Americans adopting Native children. A 1966 Bureau of Indian Affairs press release described it like this: “One little, two little, three little Indians — and 206 more — are brightening the homes and lives of 172 American families, mostly non-Indians, who have taken the Indian waifs as their own.”

It was in this context that Bert Hirsch, an attorney with the Association on American Indian Affairs, first came to Devils Lake, North Dakota, in 1967, to help a Native grandmother who’d lost custody of her 6-year-old grandson. A member of what’s now the Spirit Lake tribe, this grandmother hadn’t been accused of abuse or neglect, Hirsch told Vox. “The only allegation was that she was too old — at 62 years old,” he said.

Hirsch and the Spirit Lake tribe fought that case successfully, but it got them thinking: How many other families were going through something similar? Hirsch led an effort to gather data, first from the child placing agencies in North Dakota, and then in all 50 states, trying to glean the scope of the problem. https://ed92ffb3412518b6ff1e29ab5deef9a6.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

Prior to this, individual tribes had thought the battles they were fighting and losing to the child welfare system were unique to each of them. But Hirsch’s numbers were a wakeup call, not just to the tribes, but to national and international news outlets: The data showed that 25 to 35 percent of Native children around the country were being taken from their homes, and that 85 to 95 percent of those kids ended up in non-Native homes or institutions.

“As we pointed out to Congress over the years, it was way, way, way out of proportion to what was happening to any other demographic,” Hirsch said.

Hirsch worked as an attorney for these types of cases for four decades, and in that time, “I’ve seen a lot that makes my stomach turn, it’s just sickening,” he said. In the days before ICWA, a law that Hirsch helped to write and pass, judges “had no trouble just taking tribal kids away from their families and putting them in foster care, because they didn’t like Indians and they didn’t like their way of life. Ostensibly, they were removed for neglect, but really it was all about poverty,” Hirsch said. “If you’re poor and you’re Indian, you lose your kid.”

Although Native Americans are still overrepresented in the foster care system, ICWA stemmed the tide of removals that were severing children’s bonds to their heritage at such a widespread and alarming scale. The provisions call for a Native child’s tribe to be notified as soon as child welfare proceedings commence, and for the child’s tribe to be a party to the case in the courtroom, if they wish. Preference must be given for the child’s family — whether the family is Native or non-Native — and then to the child’s tribe, and finally, to other Native American tribes. “ICWA guides in preferences — none of them are ironclad mandates that a child be placed with an Indian family,” Hoskin, the Cherokee principal chief, said.

Hoskin said ICWA rightly respects the rights of tribes to help decide what happens to their children. “It’s just as much about the right of the tribal government to be in that courtroom as it is for that child to have their government in the courtroom,” Hoskin said. “Their culture is at stake and the future of their people is at stake.”

While the creation of ICWA was a good first step toward keeping families together, there has been no federal agency designated to oversee its implementation and ensure that states comply with the law. Because of this, no federal data has been compiled on what has resulted from the law’s passage. Also, the continued overrepresentation of Native children in the child welfare system around the country calls states’ compliance into question. In 2016, the ACLU filed a lawsuit on behalf of two South Dakota tribes challenging the state’s lack of compliance — statistics showed that Native children were 11 times more likely to end up in foster care than white children in South Dakota. A federal judge ruled the South Dakota courts were violating the stipulations of ICWA.

Hirsch said the law has been successful in reducing removals of Native children when it is followed, but that its success is based on compliance that is nowhere near universal. “The law was designed to, one, keep Indian kids from being removed from their families. That should be a goal everyone should support if you believe Indian families should continue to exist. And two, to recognize the legitimacy of Indian tribal existence,” Hirsch said. “If you believe in what this law is seeking to achieve and how it seeks to achieve it, then you can get some pretty decent compliance. But if you start from a premise that rejects all of that, it’s a different story.”

The stakes are high for Native children

What sometimes gets lost in the conversation about ICWA is that the principles it sets forth — including trying to keep family units intact if at all possible — are widely considered to be best practice in the child welfare field today. In 2013, 18 of the nation’s most prominent child welfare organizations, including Casey Family Programs, the Child Welfare League of America and the Children’s Defense Fund, filed an amicus brief in support of ICWA in another case challenging the law.

“In the Indian Child Welfare Act, Congress adopted the gold standard for child welfare policies and practices that should be afforded to all children,” the organizations wrote in the brief. “ICWA works very well and, in fact, is a model for child welfare and placement decision-making that should be extended to all children.”

“Whereas ICWA seemed like anomaly in the late ’70s when it was passed, the whole body of child welfare law has moved more and more in alignment with ICWA since,” said Kastelic, whose team at NICWA helps train child welfare workers around the country on how to implement ICWA. “Prioritizing family placements, keeping sibling groups together — ICWA was doing that in the late ’70s.”

The media’s coverage of these issues often focuses on specific cases, like those of the Brackeens, without much of the needed context of how much our failing systems contribute to the problem. Eighteen states around the country have been targets of class action lawsuitsfiled by nonprofit Children’s Rights over their poor treatment of kids in care.

The suits outline a familiar pattern: Chronic underfunding has led to low-paid and overworked caseworkers who don’t have the time they need to truly care for children’s best interests. Because of this, many kids around the country slip through the cracks, and are subject to all types of abuse while in the care of the state — sometimes worse than the conditions that led to them being in care in the first place.

With ICWA, Native kids who are disproportionately represented in the child welfare system have an added line of defense against spending long periods of time in a system that we know harms children. But the focus on individual stories over systemic problems leaves many well-meaning Americans unaware of the true scope of the problem.

“In part because of the historical underpinnings of our child welfare system, most people come at this thinking ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving.’ And most parents, who have no ability to address the structural problems they are facing … we’re still thinking about it at just a personal level,” Kastelic said.

There’s another voice missing from many of these conversations: that of the adoptee. Sandy White Hawk, a Sicangu Lakota adoptee from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, is the founder of the First Nations Repatriation Institute, which researches Native adoptees and helps to reunite them with their tribes and families.

“When we grow up in a white home in a white community, that’s all we see and know. We don’t know anything about being Native, and most white people don’t know anything about who we are,” White Hawk said. “You don’t have your image mirrored back to you in any way. That’s a distortion as you develop your identity.”

White Hawk, who experienced abuse in her adoptive home, said it’s important to recognize that all adoptions aren’t happy endings. A 2008 University of Minnesota study has shown adoptees have greater odds of an ADHD or ODD diagnosis than those who have not been separated from their families, and that adoptees are more likely to have contact with mental health professionals. In 2017, White Hawk and several others published a study of hundreds of adoptees that showed Native American adoptees were more likely to report mental health problems — including substance use disorder and recovery, eating disorders, self-harm, and suicidal ideation — than white adoptees.

“There’s nothing in our societal messages — everything about adoption is a forever happy home, and while there are happy children and there are kind and loving parents, this other reality is there, period,” White Hawk said. “And that doesn’t mean a bash of adoption. But we’re so invested in this forever-happy-saving-children thing that anything that critiques it — there’s no willingness to hear that.”

White Hawk helps organize an annual “gathering for our children and returning adoptees” powwow to help welcome Native adoptees back into their tribes. “I knew how painful and how hard it was to take your place in the circle once you’ve been gone. There was no roadmap, no one could help,” White Hawk said. “For those that may not have even met their family or have been home for a long time, it’s the first time it’s been acknowledged that they’ve suffered grief and loss.”

The Indian Child Welfare Act case has broader implications for sovereignty

The Brackeens aren’t the first to bring a case against ICWA. They’re not even the first family the Goldwater Institute has backed in such a suit. The think tank, whose funders include top Trump donors and an organization linked to the Koch brothers, has fought to dismantle union powerand to “vindicate the constitutional rights of businesses” to contribute to political campaigns.

The institute has challenged ICWA a dozen times since 2014. “The only basis for forcing these kids to be sent to tribal courts is because they’re racially connected,” Timothy Sandefur, Goldwater’s vice president of litigation, told the Nation in 2017. “It’s like saying that children of Japanese descent need to be adjudicated by the court of Japan.”

When asked for comment, the Goldwater Institute referred Vox to a blog post written by Sandefur, in which he says that Indian children “must be abused worse and for longer than children of other races before the government can rescue them from abusive households.”

As of now, the 17 Fifth Circuit judges are deliberating on the fate of ICWA; it’s likely that whatever the ruling, there will be an appeal to the Supreme Court, although it’s unclear whether the highest court will take up the case. If the Supreme Court were to agree with the plaintiffs’ assertions that ICWA is unfairly based on race, the consequences could undermine the entire concept of tribal sovereignty — and some critics of Goldwater and other conservative organizations like it say that this, and not the children’s best interests, is the point.

“I think there are critics that are specifically critical of ICWA and don’t have a broader agenda, but some do have a broader agenda. And the attacks on ICWA have very big implications,” Hoskin said. “A very basic act of sovereignty is the tribe’s ability under law to protect their children.”

In the Atlantic, two Michigan law professors argue that by seeking to dismantle ICWA, the plaintiffs “risk undoing a set of doctrines that has facilitated tribes’ ability to govern themselves and prosecute individuals who victimize Native people.”

“In Brackeen, Texas has mounted nothing less than a frontal attack on the entire corpus of federal law that governs Indian affairs today,” the professors write.

Another group vocally opposed to ICWA is the adoption industry, including the huge number of Evangelical Christians who want to adopt children. Around the turn of the century, celebrity pastors with huge followings began framing adoption as a moral imperative.

The result was a boom in the adoption industry both domestically and abroad — a 2013 surveyfound that practicing Christians are more than twice as likely to adopt than non-Christians and that American adoptions make up nearly half of all adoptions worldwide. “The regulation of adoption from state to state varies widely — and there’s a confluence of factors that mean that with quick-and-easy adoptions, there’s lots of money involved,” Kastelic said.

With the future of ICWA uncertain, tribes around the country worry about what might happen if Native children lose their special protections. “The fear is without these protections in place, we know the system continues to be biased. Bias is baked into the policies and safety assessments and you name it,” Kastelic said. “Our fear is that we are going to go back to the pre-ICWA days — the mass removal of children.”