ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) — Some members of Congress want to ensure that protections are put in place to address ongoing trauma as more information comes to light about the troubled history of Indigenous boarding schools in the United States.

A group of 21 Democratic lawmakers representing states stretching from the Southwest to the East Coast sent a letter last week to the Indian Health Service. They are asking that the federal agency make available culturally appropriate support services such as a hotline and other mental and spiritual programs as the federal government embarks on its investigation into the schools.

Agency officials said in a statement Monday they are reviewing the request and discussing what steps to take next.

Advocacy groups say additional trauma resources for Indigenous communities are more urgent than ever.

“The first step we need to take is caring for our boarding school survivors,” said Deborah Parker, a citizen of the Tulalip Tribes and director of policy and advocacy at the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland has acknowledged the process will be painful. She and many others have talked about the federal government’s attempt to wipe out tribal identity, language and culture through its boarding school policies and how that past has continued to manifest itself through long-standing trauma, cycles of violence and abuse, premature deaths, mental health issues and substance abuse.

Part of the Interior Department’s work includes identifying potential burial sites at former schools and documenting the names and tribal affiliations of the students buried there. The agency has promised to work with with tribes on how best to protect the sites and respect families and communities.

The lawmakers in their letter described the boarding school era as a “stain in America’s history.” They wrote that revisiting that history undoubtedly will be traumatic for survivors and their communities.

“We are confident that IHS is equipped to consider ways to prevent inflicting or worsening existing intergenerational trauma,” the letter reads.

The Indian Health Service noted Monday that Native American youth are 2.5 times more likely to experience trauma compared to their non-Native peers and that the agency aims to provide a “safe, supportive, welcoming, non-punitive, respectful, healthy and healing environment for all patients and staff.”

Still, it will take work to ensure services are widely available, as criticism of the Indian Health Service and chronic funding inadequacies have spanned decades and numerous presidential administrations. The pandemic exacerbated health care disparities seen in many Indigenous communities.

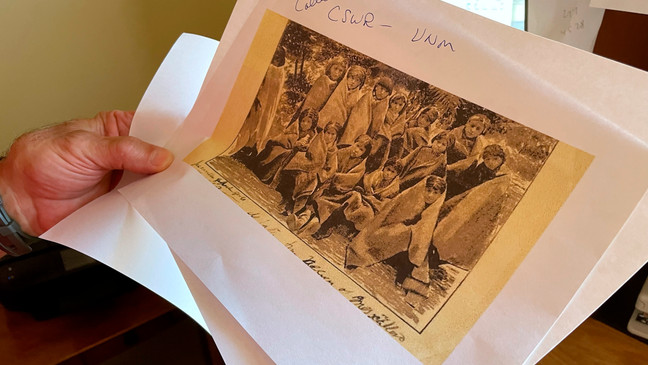

Under the Biden administration’s latest spending proposal, the agency would see a 36% increase in its annual budget for the next fiscal year. That would mark the largest single-year funding increase for the agency in decades, officials have said. About $420 million in pandemic relief funds also will be aimed at expanding mental health and substance abuse prevention and treatment services at IHS and tribal health programs. This July 8, 2021 image of material archived at the Center for Southwest Research at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, New Mexico, shows a list of names of Indigenous students who attended the Ramona Industrial School in Santa Fe. (AP Photo/Susan Montoya Bryan)

This July 8, 2021 image of material archived at the Center for Southwest Research at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, New Mexico, shows a list of names of Indigenous students who attended the Ramona Industrial School in Santa Fe. (AP Photo/Susan Montoya Bryan)

Beginning in the early 1800s, the effort to assimilate Indigenous youth into white society by removing them from their homes and shipping them off to boarding schools spanned more than a century. According to the boarding school healing coalition, hundreds of thousands of Native American children passed through boarding schools in the U.S. between 1869 and the 1960s.

While research and family accounts confirm there were children who never made it home, a full accounting of deaths at the schools has never been done.

Some tribes and others have embarked on their own investigations.

In the coming months, researchers are planning to use ground-penetrating radar at the site of a former boarding school in Utah where tribal leaders say there may be unmarked graves. Corrina Bow, chairwoman for the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, said boarding school officials would take children as young as 6 years old and force them to work at a farm on the property.